January 2025 Vol. 80 No. 1

Features

Transferring technology from control studies to field applications

By C. Vipulanandan (Vipu), Ph.D., P.E., University of Houston

(UI) — The Center for Innovative Grouting Materials and Technology (CIGMAT), a joint university-industry consortium, is not only focused on performing highly challenging research, but also communicating and educating the leaders from various large counties, cities, transportation departments, construction and oil industries, and engineers and university students, with the new innovative technologies, models.

These include artificial intelligent (AI) models, data analytics and critical infrastructure operations and maintenance related to bridges, buildings, pipelines, foundations, water supply and oil production. Also, there is increasing interest in recycling wastewater, recycling wastes and controlling carbon dioxide (CO2) emission.

CIGMAT is achieving this by organizing an annual conference and by participating in national and international conferences, presenting papers and posters. Also, some of the critical subjects and innovative new technologies are included in the teaching courses for both the undergraduate and graduate students.

Leading CIGMAT, as director, is Dr. C. Vipulanandan (Vipu), P.E., Smart Cement Inventor, professor of civil engineering, University of Houston, Houston, Texas.

CIGMAT works closely with the Texas Hurricane Center for Innovative Technology (THC-IT) related to Disaster Management and Rapid Recovery. In recent years, natural disasters and human made disasters, such as cyber-attacks, have impacted the construction industries and based on the lessons learned, it is critical to develop future plans to minimize the losses.

Some of the recent research performed at CIGMAT is focused on diversifying the new technology related to real-time monitoring of mixing of materials such as cement, concrete, drilling muds and grouts, various critical processes during construction, and also the entire service life of various infrastructures. Recent research studies also include recycling of wastewater, recycling of plastics, recycling of waste materials, treating contaminated soils and the impact of COVID-19 virus. The goals are achieved by developing new highly sensing smart materials integrated with real-time monitoring and wireless transferring for construction, maintenance, repairs and detecting gas, oil and water leaks.

Other studies include detection and quantifying corrosion of pipes and oil wells in soils, sea water and in air. Some of the studies are focused on monitoring field performances (smart cemented well, bridges supported on deep foundations), developing and characterizing smart cements, smart grouts and smart drilling muds for oil well and water well construction and cementing, ultra deepwater pipe-soil interaction, joint leak testing of storm water pipes, detection and quantification of corrosion and application of nanotechnology.

In recent years, CIGMAT researchers have developed unique testing facilities including high-pressure and high-temperature (HPHT) testing of materials for oil and gas infrastructure applications and test protocols approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to test grouts and coatings for infrastructure rehabilitations.

The Life Cycle Cost model (CIGMAT-LCC) for wastewater systems is being used by cities, counties and the public. In the past two decades, over 60 commercial products including rapid repair materials, coatings, grouts, liners, cementitious and polymer composites and pipes have been researched and tested for various applications. Microbial fuel cell technology is being further developed to treat both oily waste and recycle highly salty fracturing fluids.

The observed trends are analytically and numerically using artificial intelligent (AI) models to better understand the influence of various types of organic and inorganic contaminants and environmental parameters with the field operating conditions. Vipulanandan rheological model, Vipulanandan failure model, Vipulanandan fluid flow model and Vipulanandan fluid loss model have been developed and are being verified with CIGMAT test results and data available in the literature.

Vipulanandan Models are being used around world based on the citations listed in the Google Scholar and Web of Science citations. Also, these model predictions are compared to Artificial Neural network (ANN) and Artificial Intelligent (AI) predictive models. Every effort is being made by the CIGMAT researchers to transfer technology from control studies to real field applications.

For real-time monitoring of the materials and infrastructures performances in the field, it is very important to identify the material electrical property that can be selected for monitoring. At the CIGMAT research laboratory a new material characterization model has been developed using the two probes with the impedance-frequency response and the Vipulanandan Impedance Model to identify the critical property that can be selected for monitoring in the laboratory and field. At present, this method is being used to characterize various natural and human-made materials including fluids.

Ongoing research performed at CIGMAT is funded by federal, state and local agencies and industries. CIGMAT is working on U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and National Science Foundation (NSF)-I Corp. funded projects. These include broadening and commercializing the applications of smart cement and smart drilling mud for real-time monitoring of oil well installation and performance during the entire service life, and also in civil infrastructure applications. Funding is received from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), Texas Hazardous Waste Research Center, City of Houston and many industries (coatings, grouts, construction, pipes and oil).

In addition, smart cement is being used as the binder in developing and characterizing concrete. Several systems are being developed and integrated with artificial neural network (ANN) to monitor the performance of the cement sheath that is embedded between the casing and geological formations.

Also, research is being done on further developing the highly sensing smart cement, smart drilling fluids, smart spacer fluids and smart grouts for various applications, evaluating performance of smart grouted sand columns for monitoring earth embankments, failure theory for rocks, smart cement contaminated with clay, developing methods to treat contaminated soils and expansive clays, corrosion of steel in water, seawater and soils and also multifunctional microbial fuel cells to treat various types of wastewaters with the production of electricity and valuable byproducts.

CIGMAT conference slated for March 7

CIGMAT’s annual conference, "Infrastructures, Energy, Geotechnical, Flooding and Sustainability Issues Related to Houston and Other Major Cities," will be held March 7, at the University of Houston Hilton Hotel.

Invited speakers from major cities, transportation authorities and energy industries around the country will present and discuss projects and problems related to construction, maintenance and rehabilitation issues. The well-attended conference will also address technical issues related to maintenance and rehabilitation of water and wastewater systems, nondestructive testing methods, oil wells and pipelines, hydraulic fracturing and development of smart materials for various applications.

In addition, a number of geotechnical topics related to expansive clays, rapid construction of deep foundations and ground faulting will also be discussed.

For more information and access to Proceedings from the past 24 years of the conference, visit the CIGMAT website.

Characterizing piezoresistive smart cement modified with silicon dioxide nanoparticles using vipulanandan models

In the construction industry and petroleum industry, cement has been used for multiple applications and there is need for further enhancement of the sensing properties and mechanical properties of the cement. In the construction industry it is used as a binder in various types of grouts and concrete to construct deep foundations, pipes, bridges, highways, storage facilities, tunnels and buildings.

In the oil industry, cement is typically utilized to fill the annular space between the casing and rock formation by displacing the drilling fluid. Also, cement will support the casing and protect it against corrosion and impact loading, restrict the movement of fluids between formations, and isolate productive and nonproductive zones.

One of the important additives in cement is silica, which has been used in a certain amount to mitigate strength degradation. As deepwater exploration and production of oil and gas expand around the world, there are unique challenges in good construction, beginning at the seafloor. Moreover, the real-time monitoring of the changes in the cement in-situ is critical to evaluate the performance of the cemented infrastructures and wells.

Recent case studies on cementing failures have clearly identified several issues that resulted in various types of delays in the cementing operations. The catastrophic accident in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010 was one of the world’s worst oil spills. Two studies performed during the period of 1971 to 1991 and 1992 to 2006 clearly identified cement failures as the major cause for blowouts. Cementing failures increased significantly during the second period of study, when 18 of the 39 blowouts were due to the cementing problems Therefore, proper monitoring and tracking the entire process of the cement in situ becomes important to ensure cement integrity during the service life of the infrastructures and well.

Electrical response characteristics measurement has appropriate sensitivity in monitoring the characteristics of cementitious materials. The advantages of using this technique include its accuracy, easy test procedure, and nondestructive characteristics. Additionally, this method can be used for monitoring the long-term behavior of cement in practice. The electrical resistivity of cement is affected by a number of factors, such as pore structure (continuity and tortuosity), pore solution composition, cementitious content, water-to-cement ratio, moisture content, and temperature.

Moreover, the electrical resistivity of cement is dramatically affected by contaminations, due to the resistivity contrast between cement and the contaminating substance. Recent studies have also shown that the changes in resistivity (electrical piezoresistivity strain) in the piezoresistive smart cement at peak compressive stress were over 1000 times (100,000 percent) higher than the mechanical strain in the materials. Hence, instead of the mechanical strain, the change in resistivity (electrical piezoresistivity strain) has the potential to be used to determine the integrity of the materials.

A new method has been developed to measure the electrical resistivity of the materials using the two-probe method with alternative current. LCR meters (measures the inductance (L), capacitance (C) and resistance (R)) were used at 300 kHz frequency to measure the changes in the bulk resistance.

Use of nanoparticles in the areas of medicine, science and engineering are rapidly increasing because of multiple benefits based on the size, shape and chemical compositions of the nanoparticles. With the advancement of nanotechnology, several of these materials can be used to solve some of the problems encountered in cementing.

Nano silica is a versatile nanomaterial used as drug carriers in medicine, fillers in polymers and fertilizer/pesticide carriers and potentially bioavailable source of silicon in agriculture. Based on the improved compressive strength, it is clear that NanoSiO2 behaves not only as a filler to improve the cement microstructure, but also to promote the pozzolanic reactions. Therefore, it is of interest to add NanoSiO2 particles to the smart cement mixtures to enhance the performance of the cement and concrete.

The overall objective of this study was to investigate the effects of up to 1 percent of NanoSiO2 on the modified smart cement behavior. Specific objectives were as follows:

• Investigate and quantify the changes in the electrical resistivity during the curing time and compressive behavior of the NanoSiO2 modified smart cement.

• Model the curing, compressive stress-strain, and compressive piezoresistive behavior of the NanoSiO2 modified smart cement using Vipulanandan Models.

Materials and Methods

Silicon dioxide nano powder (NanoSiO2), with the grain size of 12 nm and specific surface area of 175 to 225 m2/g (from supplier datasheet), was selected for this study.

The smart cement sample’s water-to-cement (w/c) ratio was 0.38. To improve the sensing properties and piezoresistive behavior of the smart cement, it was modified with 0.1 percent of carbon fillers (CF) by weight of cement and mixed in all of the samples. Three series of smart cement slurries were prepared with NanoSiO2 up to 1 percent (by the weight of the cement) and tested up to 28 days of curing.

A total of 0.1 percent of carbon fibers (CF) was added with the cement mix as the base modification. The CF used in this study was about 10 m in diameter. NanoSiO2 was added to the smart cement in the mixer with the mixing intervals of 20 sec at 4000 rpm. Cement, water, and additives (0.1 percent CF and NanoSiO2) were mixed at the speed of 4000 rpm for 3 minutes and 35 seconds at the speed of 1200 rpm. The two wires were placed in the mold and at a vertical distance of 50 mm between them.

The embedment depth of the wire in the specimen was about 25 mm. For setting time monitoring and compressive stress tests, cylinders with the diameter of 50 mm (2 inches) and a height of 100 mmm (4 inches) were prepared. For quick property changes monitoring, a two-probe method was selected. During the initial stages of setting, conductivity and API resistivity meters were used to determine the curing cement resistivity and using Eqn. (1) the calibration parameter K was obtained with time

The average value of parameter K was 56.5 m-1. In order to have consistent results, at least three specimens were prepared for each type of mix.

Density of smart cement with and without NanoSiO2 was measured immediately after mixing using the standard mud balance cup.

Two different instruments were used to measure the electrical resistivity of the smart cement:

• A commercially available conductivity probe was used to measure the conductivity (inverse of electrical resistivity) of the cement slurry and the measuring range was 10,000 Ω-m to 0.1 Ω-m.

• A commercially available digital resistivity meter was used to measure the resistivity of the slurries, and semi-solids with resistivities in the range of 0.01Ω-m to 400 Ω-m. Both of the electrical resistivity devices were calibrated using standard solutions of sodium chloride (NaCl).

Based on past studies, electrical resistivity was selected as a monitoring parameter to quantify the performance of modified cement during curing and hardening process. The electrical resistivity of the slurries was measured using an API standard resistivity meter. Further, electrical resistance was measured using an inductance, capacitance, and resistance (LCR) meter during the curing time.

To minimize the contact resistances, the resistance was measured at 300 kHz using the two-wire method. Each specimen was calibrated to obtain the electrical resistivity (ρ) from the measured electrical resistance (R) based on the Eqn. (1).

R=ρ∗(LA)=ρKR=𝜌∗LA=𝜌K

(1) where L is the distance between the wires, A is the cross-sectional area through which the current is flowing, and L/A is the “nominal geometry factor.” In insulator material, such as cement, the actual pathway of the current is not well defined as compared to the conductive material such as metals.

Hence, L/A in Eqn. (1) was replaced by an experimentally determined calibration factor (K), by measuring the bulk resistance (R) and the resistivity () of the material at the same time. Also, normalized change in resistivity with the changing conditions (curing, stress) can be represented as follows:

Δρ ρ= ΔRR𝛥𝜌 𝜌= 𝛥RR

(2)

In this study modified cement materials are represented in terms of resistivity (ρ) to the changes (composition, curing and stress) since it has been shown to be a sensitive parameter.

Compressive strength test (ASTM C 39). The cylindrical specimen with a diameter of 2 inches and a height of 4 inches (50mm Dia.*100 mm height) was capped (sulfur capping) and tested at a predetermined controlled displacement rate. Compression tests were performed on cement samples after 1 day, 7 days and 28 days of curing using a hydraulic compression testing machine. Also 10 mm in length stain gages with initial resistance of 120 Ω were used to measure the axial strain.

Piezoresistivity test. Piezoresistivity describes the change in the electrical resistivity of a material under pressure. Since oil well cement serves as the pressure-bearing part of wells in real applications, the piezoresistivity of modified and unmodified cement was investigated under compressive loading. During compression testing, electrical resistance was measured in the stress axis. To eliminate the polarization effect, alternating current resistance measurements were made using an LCR meter at a frequency of 300 kHz.

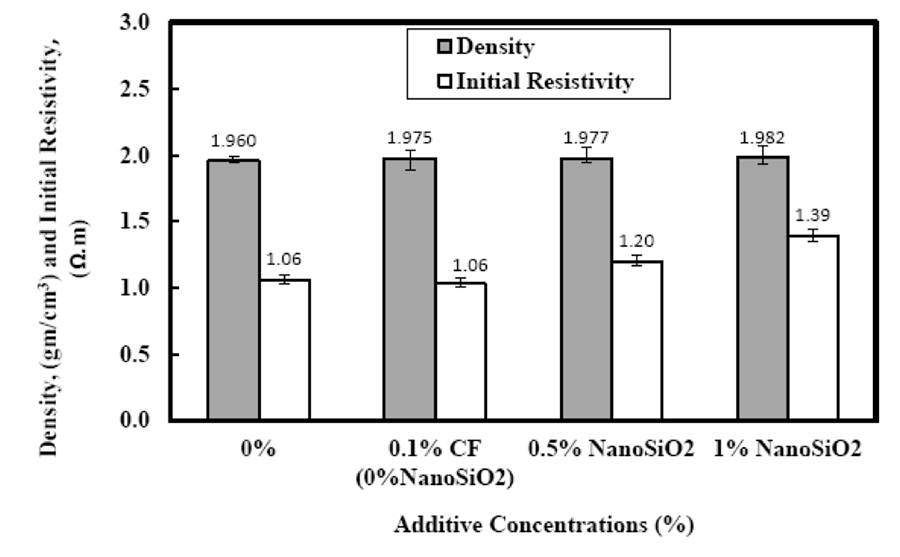

The average density of smart cement with less than 0.1 percent carbon fiber was 1.975 g/cc (16.47 ppg). The initial electrical resistivity (ρo) of the smart cement mix with a w/c ratio of 0.38 was1.06 Ωm.

The average density of the smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 was 1.977 g/cc (16.49 ppg), 0.1 percent increase in density. The initial electrical resistivity (ρo) of smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 was 1.20 Ωm, a 13 percent increase in the electrical resistivity as shown in Figure 1. The resistivity was more sensitive to the NanoSiO2 addition than the density.

The average density of the smart cement with 1 percent NanoSiO2 was 1.982 g/cc (16.53 ppg), about a 0.4 percent increase in density. The initial electrical resistivity (ρo) of smart cement with 1.0 percent NanoSiO2 was 1.39 Ωm, a 31 percent increase in the electrical resistivity as shown in Figure 1. The resistivity was more sensitive to the 1 percent NanoSiO2 addition than the density.

Figure 1. Effect of 1 percent NanoSiO2 on the density and initial resistivity of smart cement

Change in the electrical resistivity with time and the minimum resistivity quantifies the formation of solid hydration products, which leads to a decrease in the porosity and influences the cement strength development.

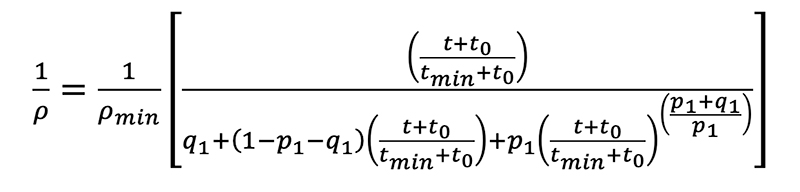

Based on experimental results, the model proposed by Vipulanandan was used to predict the electrical resistivity of smart cement during hydration up to 28 days of curing as shown in Figure 2 . The curing model is defined as follows:

(3)

where r: electrical resistivity (Ω-m); rmin: minimum electrical resistivity (Ω-m); tmin: time corresponding minimum electrical resistivity (rmin);

p1, p1,

to, and q1 are model parameters and time (minutes).

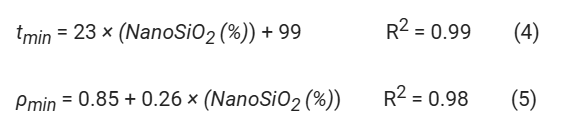

The minimum resistivity (ρmin) of smart cement was 0.85 Ωm and the time to reach the minimum resistivity (tmin) was 99 minutes, as summarized in Table 1. The resistivity after 24 hours was 3.90 Ωm, representing a change of about 268 percent in 24 hours, as shown in Figure 2 (a). The resistivity index (RI24hr) for smart cement, 364 percent, represents the maximum resistivity change in 24 hours, as summarized in Table 1.

The resistivity after 7 days and 28 days was 7.7 Ωm and 35.7 Ωm, respectively and also shown in Figures 2 (b) and (c). These observed trends clearly indicate the sensitivity of resistivity to the changes occurring in the curing of cement as summarized in Table 1.

The minimum resistivity (ρmin) of smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 was 0.95 Ω-m, which was 12 percent higher compared to the smart cement minimum electrical resistivity. The time to reach the minimum resistivity (tmin) was 110 minutes, as summarized in Table 1, and 11 percent higher than the smart cement.

The resistivity after 24 hours was 4.16 Ωm, representing a change of about 289 percent in 24 hours, as shown in Figure 2 (a). The resistivity index (RI24hr) for smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 was 338 percent, as summarized in Table 1. The resistivity after 7 days and 28 days was 8.0 Ωm and 27.8 Ωm respectively and also shown in Figures 2(b) and 2(c). Change in RI24hr decreased with the 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 content.

These observed trends clearly indicate the sensitivity of resistivity to the changes occurring in the curing of cement, as summarized in Table 1.

The minimum resistivity (ρmin) of smart cement with 1 percent of NanoSiO2 was 1.11 Ω-m, which was about 30 percent higher compared to the smart cement minimum electrical resistivity. The time to reach the minimum resistivity (tmin) was 122 minutes, as summarized in Table 1, which was about 23 percent higher than the smart cement. The resistivity after 24 hours was 4.76 Ωm, representing a change of about 242 percent in 24 hours, as shown in Figure 2 (a).

The resistivity after 7 days and 28 days were 8.7 Ωm and 20.6 Ωm, respectively and also shown in Figures 2(b) and 2(c). The resistivity index (RI24hr) for smart cement with 1 percent of NanoSiO2 was 328 percent, as summarized in Table 1. Change in RI24hr decreased with 1 percent NanoSiO2 content. These observed trends clearly indicate the sensitivity of resistivity to the changes occurring in the curing of cement, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Curing bulk resistivity parameters for smart cement with NanoSiO2

NanoSiO2

Vipulanandan curing model (Eqn. (3)) was used to predict the resistivity changes with the curing time for 1 day, 7 days and 28 days of curing, as shown in Figure 2. The model predicted the experimental results very well. The model parameters p1, q1 and the ratio q1p1/q1p1 were all sensitive to the amount of NanoSiO2 added to the cement. Also, the parameters tmin and min can be used as quality control indices and were related to the NanoSiO2 content as follows:

Hence, the electrical resistivity parameters were linearly related to the NanoSiO2 content.

Figure 2. Bulk electrical resistivity development of smart cement with various amount of NanoSiO2 (a) 1 day (b) 7 days and (c) 28 days

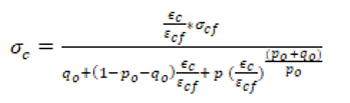

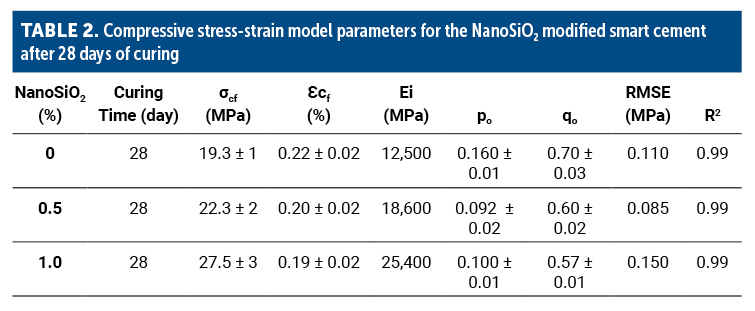

Based on the experimental results, Vipulanandan p-q stress-strain model (Eqn. (6)) was used to predict the compressive stress-strain relationship for smart cement with and without NanoSiO2 and the relationship is as follows:

(6)

where: c is compressive stress and c compressive strain; scf and ecf are compressive strength and corresponding strain, as summarized in Table 2. The model parameters po, and qo are also summarized in Table 2. Model parameters po and qo increased with curing time based on the NanoSiO2 content. The compressive stress-strain relationships for the cement with and without nanoSiO2 are shown in Figure 3.

The compressive strengths (cf) of the smart cement after 28 days of curing were 19.3 MPa, as shown in Figure 3. The failure strain was 0.22 percent and the initial modulus was 12,500 MPa, as summarized in Table 2. The model parameters qo and po were 0.70 and 0.160, respectively. The parameter qo represents the nonlinearity up to peak stress, and the smart cement had the highest linearity, highest value of parameter qo, as shown in Figure 3. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.110 MPa, as summarized in Table 2.

The compressive strengths (cf) of the smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 after 28 days of curing was 22.3 MPa, 15.5 percent higher than the smart cement without NanoSiO2, as shown in Figure 3. The failure strain was 0.20 percent and the initial modulus was 18,600 MPa, as summarized in Table 3.

The addition of 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 to the smart cement reduced the failure strain and increased the modulus compared to the smart cement without NanoSiO2. The model parameters qo and po were 0.60 and 0.092, respectively. The parameter qo represents the nonlinearity up to peak stress, and was lower than the smart cement without NanoSiO2, as shown in Figure 3. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.085 MPa, as summarized in Table 2.

The compressive strengths (cf) of the smart cement with 1 percent NanoSiO2 after 28 days of curing was 27.5 MPa, 42.5 percent higher than the smart cement without NanoSiO2, as shown in Figure 3. The failure strain was 0.19 percent and the initial modulus was 25,400 MPa, as summarized in Table 2. The addition of 1 percent NanoSiO2 to the smart cement reduced the failure strain and doubled the modulus, 100 percent increase compared to the smart cement without NanoSiO2. The model parameters qo and po were 0.57 and 0.100, respectively. The parameter qo represents the nonlinearity up to peak stress and was lower than the smart cement without NanoSiO2 as shown in Figure 3. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.150 MPa, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Compressive stress-strain model parameters for the NanoSiO2 modified smart cement after 28 days of curing

Figure 3. Compressive stress-strain relationship of modified smart cement with 28 days of curing

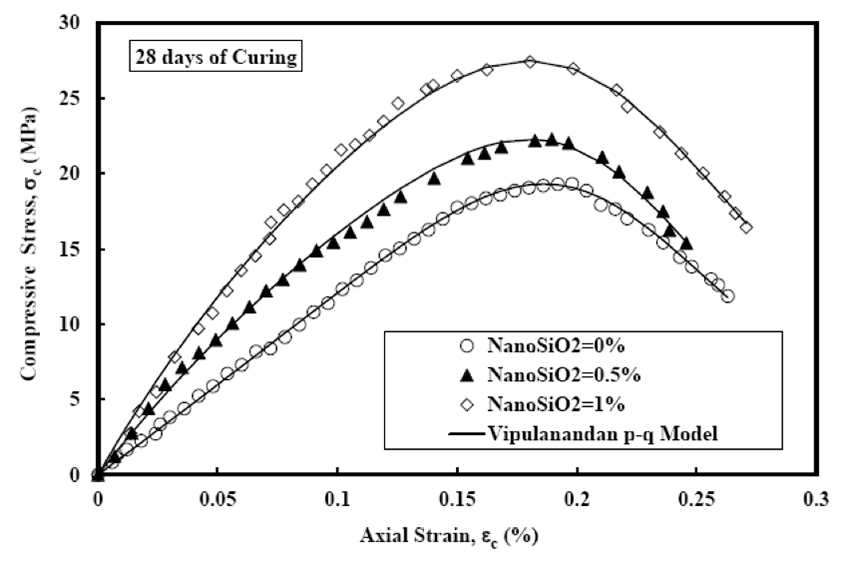

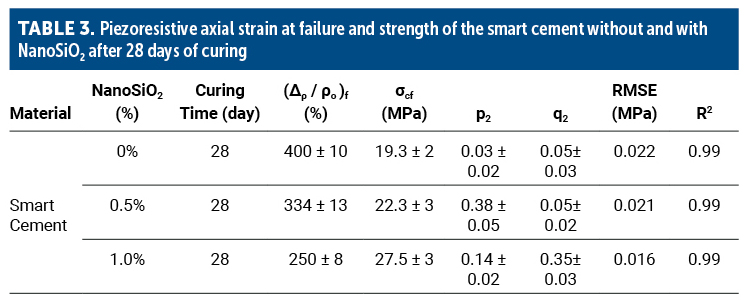

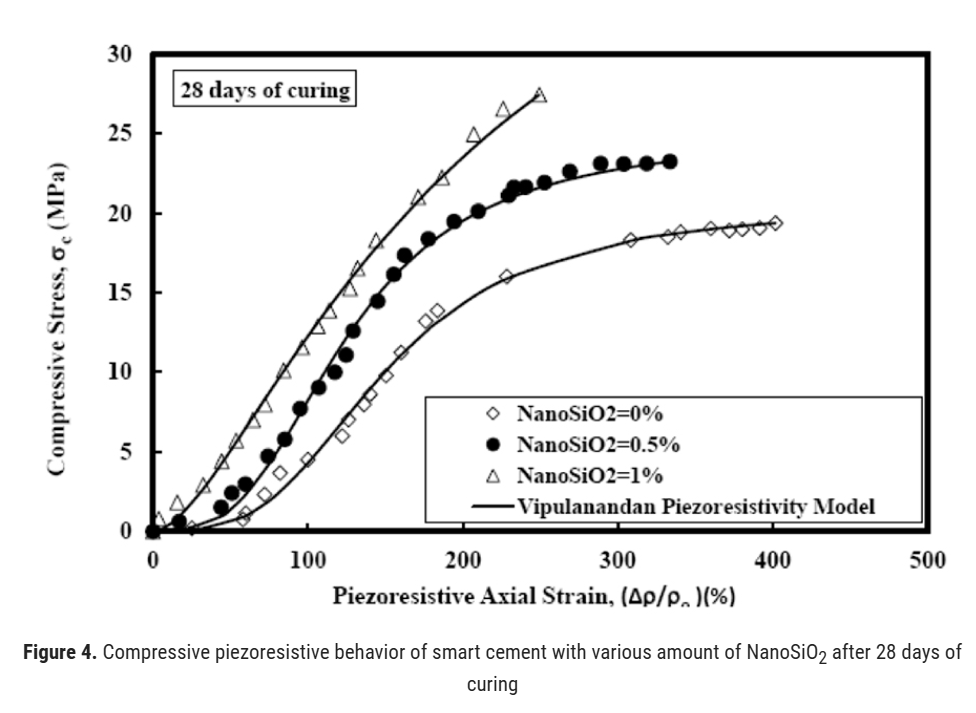

Based on experimental results, Vipulanandan p-q piezoresistivity model was developed to predict the change in electrical resistivity of the smart cement during applied compressive stress for 28 days of curing. The Vipulanandan Piezoresistive model is defined as follows:

where sc is the stress (MPa); scf is the compressive strength at failure (MPa);

x=(Δρρo)∗100 x=∆𝜌𝜌o∗100

is the percentage piezoresistive axial strain due to the applied stress;

xf=(Δρρo)f∗100 :xf=∆𝜌𝜌of∗100 :

Percentage piezoresistive axial strain at failure; ∆r: change in electrical resistivity; ro : initial electrical resistivity (s = 0 MPa) and p2 and q2 are the piezoresistive model parameters.

The piezoresistive axial strain of the smart cement at failure

(Δρρo)f∆𝜌𝜌of

after 28 days of curing was 400 percent, as summarized in Table 3 and shown in Figure 4. Compressive piezoresistive axial strain at failure reduced by 23 percent after 28 days of curing. The compressive axial failure strain was 0.22 percent, so the piezoresistive axial strain has been increased by 1,818 times (181,800 percent), making the smart cement to be highly sensing.

The model parameters q2 and p2 were 0.05 and 0.03 respectively. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.022 MPa as summarized in Table 3.

The piezoresistive axial strain of the smart cement with 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 at failure

(Δρρo)f∆𝜌𝜌of

after 28 days of curing was 334 percent, as summarized in Table 3 and shown in Figure 4. Compressive piezoresistive axial strain at failure reduced by 32.5 percent after 28 days of curing and the percentage reduction was higher than the smart cement without NanoSiO2. Addition of 0.5 percent NanoSiO2 reduced the piezoresistive axial strain of smart cement by 16.5 percent.

The compressive axial failure strain was 0.20 percent, so the piezoresistive axial strain has been increased by 1,670 times (167,000 percent) making the smart cement to be highly sensing. The model parameters q2 and p2 were 0.05 and 0.38, respectively. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.021 MPa, as summarized in Table 3.

The piezoresistive axial strain of the smart cement with 1 percent NanoSiO2 at failure

(Δρρo)f∆𝜌𝜌of

after 28 days of curing was 250 percent, as summarized in Table 3 and shown in Figure 4. Compressive piezoresistive axial strain at failure reduced by 41.6 percent after 28 days of curing and the percentage reduction was higher than the smart cement without NanoSiO2. Addition of 1 percent NanoSiO2 reduced the piezoresistive axial strain of smart cement by 37.5 percent.

The compressive axial failure strain was 0.19 percent, so the piezoresistive axial strain has been increased by 1,316 times (131,600 percent) making the smart cement to be highly sensing. The model parameters q2 and p2 were 0.35 and 0.14 respectively. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.99 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) was 0.016 MPa, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Piezoresistive axial strain at failure and strength of the smart cement without and with NanoSiO2 after 28 days of curing

Figure 4. Compressive piezoresistive behavior of smart cement with various amount of NanoSiO2 after 28 days of curing

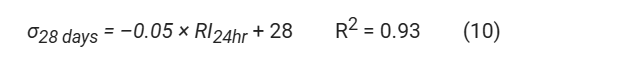

During the entire cement hydration process, both the electrical resistivity and compressive strength of the cement increased gradually with the curing time. For cement pastes with various NanoSiO2 content, the change in the resistivity varied during the hardening. The cement paste without NanoSiO2 had the highest electrical resistivity change (RI24hr), as summarized in Table 2. The linear relationship between (RI 24hr) and the 28 days compressive strengths (MPa) is as follows:

Conclusions

Based on the experimental and analytical study on the smart cement modified with silica nanoparticles (NanoSiO2) up to 1 percent, the following conclusions are advanced:

• Addition of 1 percent NanoSiO2 increased the compressive strength of the smart cement by 42 percent after 28 days of curing. Also, the modulus of elasticity of the smart cement increased with the additional of 1 percent NanoSiO2. Vipulanandan p-q stress-strain model predicted the behavior very well.

• Resistivity was sensitive to the amount of NanoSiO2 used to modify the smart cement. The amount of NanoSiO2 can be detected based on the change in the initial resistivity. An addition of 1 percent NanoSiO2 increased the initial electrical resistivity (ρo) of smart cement by 35 percent and increased the time to reach minimum resistivity by 31 minutes. Initial electrical resistivity can be used as a good indicator for quality control. Vipulanandan p-q curing model predicted the behavior very well.

• Addition of the NanoSiO2 reduced the piezoresistivity strain at peak stress of the smart cement. Vipulanandan p-q piezoresistive model predicted the behavior very well.

• Linear correlation was found between resistivity index (RI24) and the compressive strength after 28 days of curing.

New Rapid Nondestructive Testing Method for Detecting and Quantifying Steel Corrosion in Saltwater and Clay Soil using the Vipulanandan Impedance Corrosion Model

Steel is used as a construction material both onshore and offshore. In order to improve the maintenance operations and also extend the service life of oil and gas wells, petrochemical plants and supporting infrastructures, it is very important to detect and quantify corrosion real-time. Corrosion degrades the material by bio-chemical reactions, stress fatigue degradation, temperature cycles with the exposed environments. In addition to daily encounters with this kind of degradation, corrosion causes failures, fire hazards due to pipeline leakages, plant shutdowns, waste of valuable resources, loss and contamination of product, reduction in productivity and expensive maintenance.

Corrosion of metals alone cost the U.S. economy more than $300 billion per year. Approximately one-third of this could be saved by proper corrosion detection and quantification. NACE has reported that losses due to corrosion are equal to 1-5 percent of the country’s Gross National Product (GNP) which sums up to several billion dollars. The annual cost of corrosion in the USA oil and gas industry is over $27 billion and globally $60 billion.

One of the essential contributions to theories of corrosion was made by Faraday (1791- 1867), who established a measurable relationship between chemical activity and electrical current. Ideas on corrosion control began to be produced at the start of the 19th century. Evans (1923) provided a modern-day understanding of the reasons and the control of corrosion, based upon his classic electrochemical theory. Now there are many testing standards for corrosion developed by professional societies such as ASTM.

The overall objective was to verify the sensitivity of the new nondestructive two probe alternative current method to detection and quantify the surface and bulk corrosion using steel specimens. Specific objectives were as follows:

- Identify the equivalent electrical circuits for the surface and bulk corrosion of steel and represent them in terms of electrical properties of the material using the impedance frequency relationship.

- Investigate the corrosion development (surface and bulk separately) with time for steel specimens placed in 3.5 percent salt solution, and quantify the surface and bulk corrosion along the length of the steel specimens.

- Investigate the corrosion development on the surface of steel pipe placed in moist bentonite clay.

- Compare the standard test results, such as weight loss, and visual inspection due to corrosion, with the new nondestructive test method where changes in the electrical properties used to quantify the corrosion.

Materials and Methods

Corrosion of carbon steel, ASTM A1018, was used for this study. Based on the manufacturer’s data sheet, the iron content varied from 98.8 percent to 99.3 percent with a carbon content of 0.18 percent. For the weight loss and potential difference study, the samples were 3 inches in length. For the electrical characterization of corrosion, the steel bars were 30 inches in length 1.2 inches wide and 0.16 inch thick. Also, two-inch diameter steel pipe was buried in the bentonite clay to evaluate the corrosion. The specific gravity of the carbon steel is 7.86 (ASTM G1-03).

Both, 3.5 percent sodium chloride (NaCl) salt solution represents the sea water and for the accelerated test, 10 percent sodium chloride (NaCl) solution represents the hydraulic fracturing fluids with high salt contents. The steel specimens were placed in the selected solution and bentonite clay in a plastic container for the entire duration of testing.

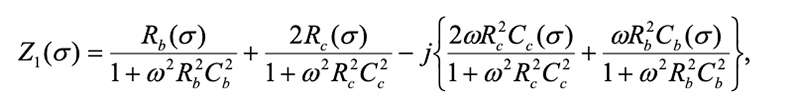

It is importnat to clearly identify the electrical properties (resisitivity (representing resisitance R), permitivity( representing capacitance, C) and permeabilty (representing inductance, L)) of the material that will represnt the corroding material. Identification of the most appropriate equivalent circuit to represent the electrical properties of a material is essential to further understand its properties and the changes due to corosion. In the literature, there are data on impedance frequency responses of materials, but there are no clear electrical properties that influence the response.

In this study, different possible equivalent circuits were analyzed to find an appropriate equivalent circuit to represent the corroding steel with two probe monitoring.

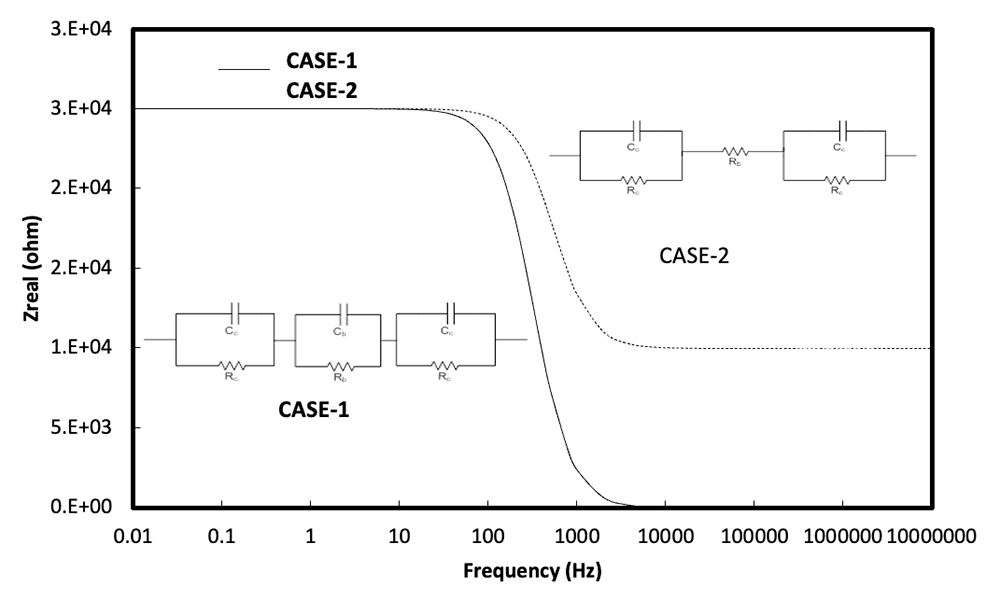

CASE 1: General Bulk Material – Resistance and Capacitor

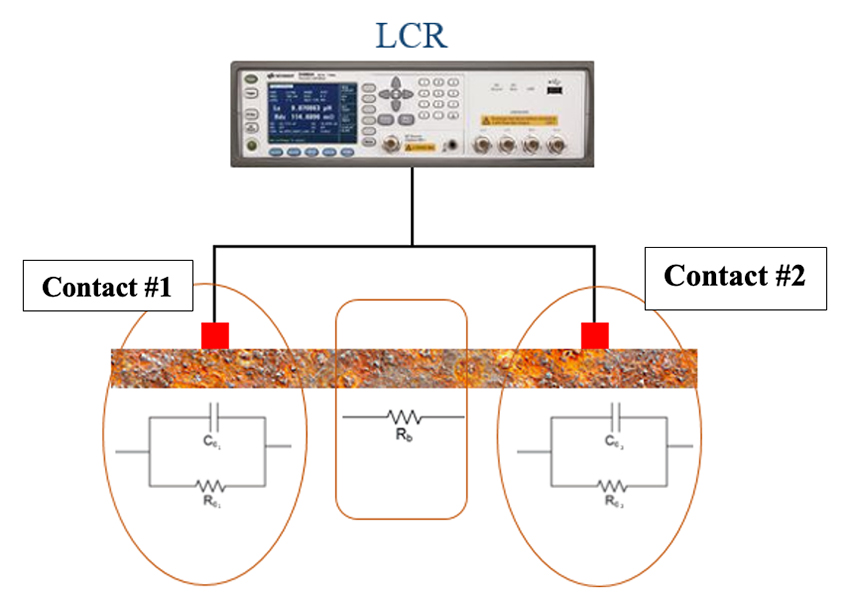

In the equivalent circuit for CASE 1 (Fig. 5), the contacts were connected in series, and both the contacts and the bulk material were represented using a capacitor and a resistor connected in parallel (Fig. 5).

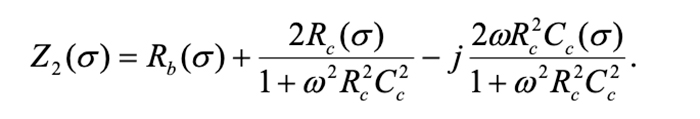

In the equivalent circuit for CASE 1, Rb and Cb are resistance and capacitance of the bulk material, respectively and Rc and Cc are resistance and capacitance of the contacts, respectively. Both contacts are represented with the same resistance (Rc) and capacitance (Cc), as they are identical.Total impedance of the equivalent circuit for Case 1 (Z1) can be represented as follows:

where ω is the angular frequency of the applied signal. When the frequency of the applied signal was very low, ω → 0, Z1 = Rb + 2Rc, and when it is very high, ω → ∞, Z1= 0.

Figure 5. Comparison of typical responses of equivalent circuits for CASE 1 and CASE 2.

CASE 2: Special Bulk Material - Resistance Only

In CASE 2 (Fig. 5), as a special case of CASE 1, the capacitance of the bulk material (Cb) was assumed to be negligible.

The total impedance of the equivalent circuit for CASE 2 (Z2) is as follows:

When the frequency of the applied signal was very low, ω → 0, Z2 = Rb + 2Rc, and when it is very high, ω → ∞, Z2 = Rb (Fig. 5).

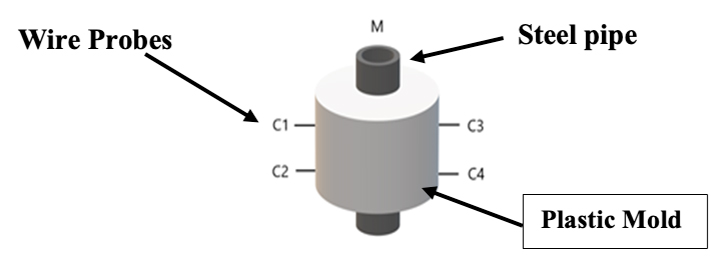

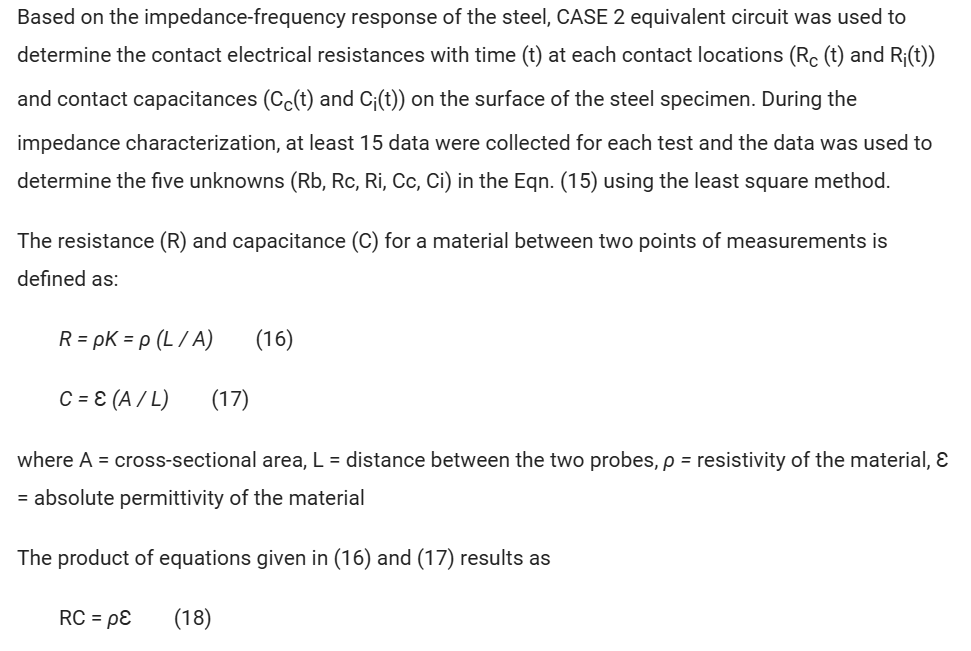

The pipe was placed in moist (40 percent) bentonite clay and the configuration is shown in Figure 6. The changes in the steel pipe surface were monitored by connecting one probe to the steel pipe and the other to one of the wire probes (C1, C2, C3, C4).

Figure 6. Steel pipe placed in Bentonite clay placed in an instrumented plastic mold

Results, Verification and Discussion

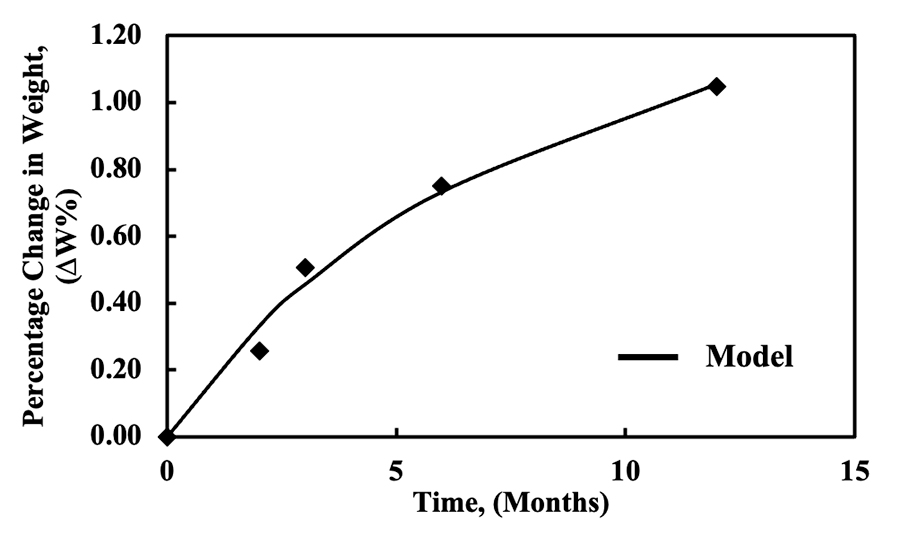

Method 1: Weight Loss Study (ASTM G1-03). Steel samples with an initial length of 75 mm, width of 30 mm and thickness of 4 mm were used for this experiment. Six specimens were tested. Specimens were placed in 10 percent sodium chloride solution and tested regularly by cleaning the specimens and measuring the weight and dimensions.

The initial average weight was 812.1 g and it reduced to 803.6 g in one year. The specimens were cleaned using mechanical tools and were measured after 2, 3, 6 and 12 months. The percentage weight change was related to the testing time (t) (Fig. 7) using the Vipulanandan correlation model (Eqn. (13)) and the relationship is as follows:

ΔW × 100W= tA+Bt∆W × 100W= tA+Bt

(13)

where W was the initial weight of the specimen and DW was the weight change. The weight change after one year was 1.05 percent. The model predicted the test results very well with a coefficient of verification (R2) of 0.99. The parameter A was 4.98 months/ percent and parameter B was 0.53/ percent. So, the ultimate predicted weight change will be 1.88 percent when the time of exposure is very large (time is infinity).

Figure 7. Variation of weight loss for the steel with time in 10 percent NaCl solution

Using the ASTM G1-03 standard, the corrosion rate (mm/year) was determined using the following relationship:

Corrosion Rate=K ×ΔWArea ×Time (hours)×Density Corrosion Rate=K ×∆WArea ×Time (hours)×Density

The carbon steel density was 7.86 g/cm3 and the K parameter for estimating the corrosion rate in mm/year was 8.76x104. The estimate corrosion rate using Eqn. (14) was 1.54 mm/year or 0.06 inches/year in 10 percent NaCl solution. The estimated rate of corrosion was about three times the corrosion rated reported for sea water (3.5 percent NaCl) in the literature and, hence, the results are comparable.

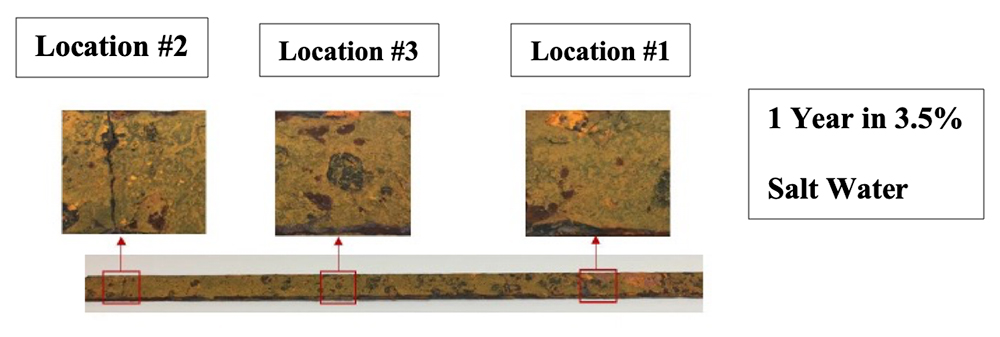

Method 2: Visual Inspection Study. The 750-mm-long steel specimens placed in 3.5 percent NaCl (salt) solution were visually inspected on a regular basis. Images of the corroded steel surfaces along the length in three locations are shown in Fig. 8; the corrosion was not uniform, and it changed from point to point.

As shown in Fig. 8, Locations #2 and #3 showed more corrosion than Location #1. For the new NDT method, Locations #1 and #2 were used as the Contacts #1 and #2, respectively.

Figure 8. Visual inspection of surface corrosion of corroded specimen

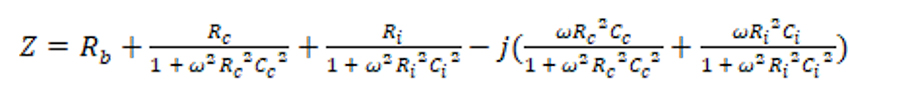

Method 3: New Nondestructive Two Probe Resistivity Study (U.S. Patent 2020). The 30-inch long steel specimens placed in 3.5 percent NaCl solution and steel pipe in clay were tested regularly to detect and quantify corrosion using the two probe alternative current method (Fig. 9). The alternative current frequency varied from 20 Hz to 300 kHz.

Figure 9. Testing configuration for the new NDT resistivity method

The responses for both non-corroded and corroded steel were CASE 2. This is the identification of the impedance circuit for the current corrosion study (Figure 10 and Eqn. (15)).

(15)

Figure 10. Vipulanandan Corrosion Impedance Model Circuit.

Since

ρ and ϵ𝜌 and 𝜖

in equations (16) and (17) are material properties, RC at the point of contact is also material property and will be referred as electrical corrosion index. This parameter can be used in characterizing the surface corrosion at each point.

The electrical resistivity (r) of the bulk steel specimen was determined from the Rb measured along the length of specimen between the two points of contact and using the Eqn. (15). The initial resistivity of non-corroded steel ρ0 =1.59 E-07 Ωm and Ro is the initial resistance measured.

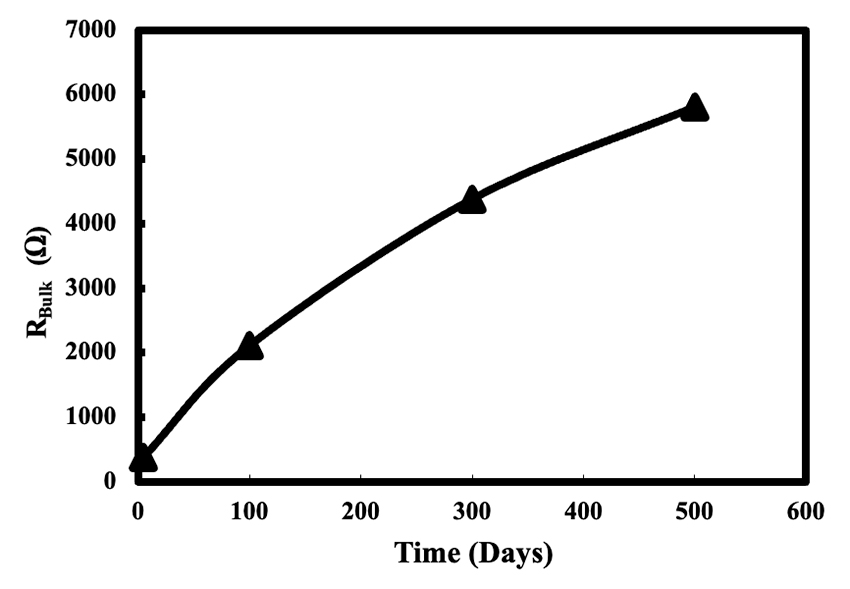

The impedance-frequency measurements were performed on a weekly basis for 500 days. The frequency range used was from 20 Hz to 300 kHz. The bulk resistance (Rb(t)) increased non-linearly with time as shown in Fig. 11. After 500 days of corrosion, the bulk Rb(t) along the length of the corroded steel between Contact #1 (Location #1) and Contact #2 (Location #2) (2 feet apart, Fig 8) increased from 0.131Ω to 5810 Ω which showed a change of 44,351 (4,435,100 percent).

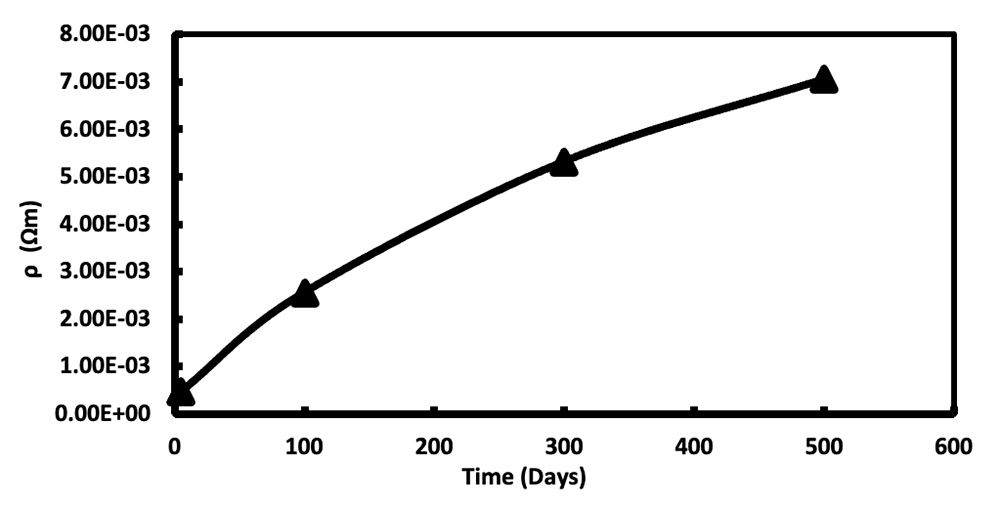

The resistivity of the corroding steel changed from 1.59 x10-7 Ωm to 7.05 x10-3 Ωm along the 2 feet length during the testing period of 500 days (Fig. 12), the change is 44,340 times (4,434,000 percent), which indicated the resistivity was a highly sensing material property to represent the corrosion level within the bulk steel. The change in the electrical resistivity, a material property, is part of the corrosion of the steel, but could not be quantified by any other standard test methods.

Figure 12. Variation of Electrical Resistivity of the Bulk Steel with Time in 3.5 percent NaCl Solution.

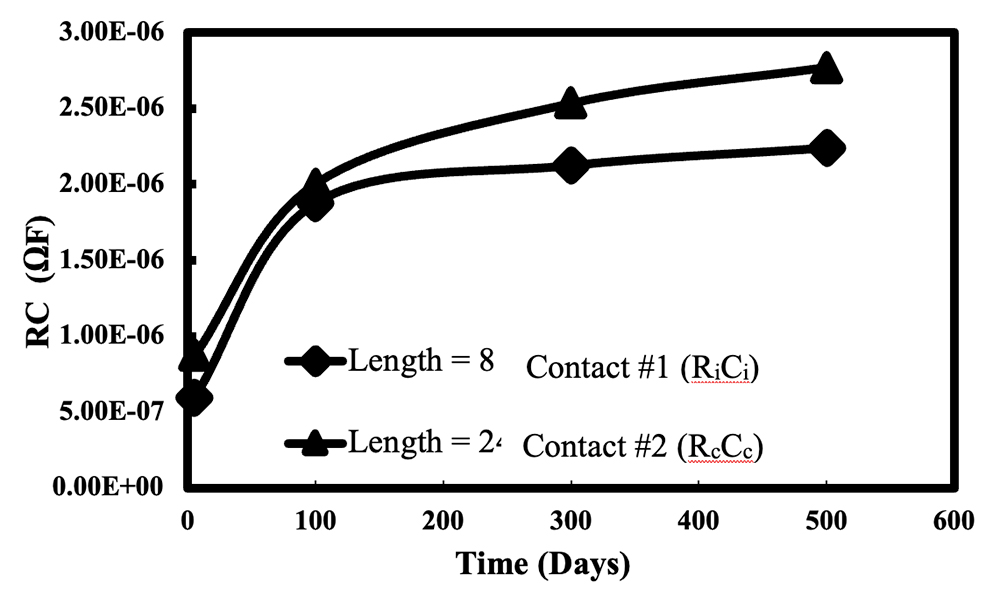

The variation of contact corrosion index, material property (R*C), for the corroding steel at Contact #1 in 3.5 percent NaCl solution is shown in Figure 13. From the Fig.8, the rust material on the surface of the corroding steel increased with time. The RCCC at Contact #1 increased from 5.97 E-07 ΩF to 2.24 E-06 ΩF during the testing period of 500 days, a 2.75 time (275 percent) increase.

The Contact #2 corrosion index parameter RiCi increased from 8.72E-07 ΩF to 2.77E-06 ΩF as shown in Fig. 13. The contact index parameter increased by 2.2 times (220 percent). The corrosion index parameter after 500 days of testing at Contact #2 was higher than Contact #1, by about 24 percent. The corrosion index clearly quantified the surface conditions at the measured points and the two points were not the same; also, the visual inspection showed the difference on the surface.

Figure 13. Corrosion index parameters for the two contact locations in Fig.8

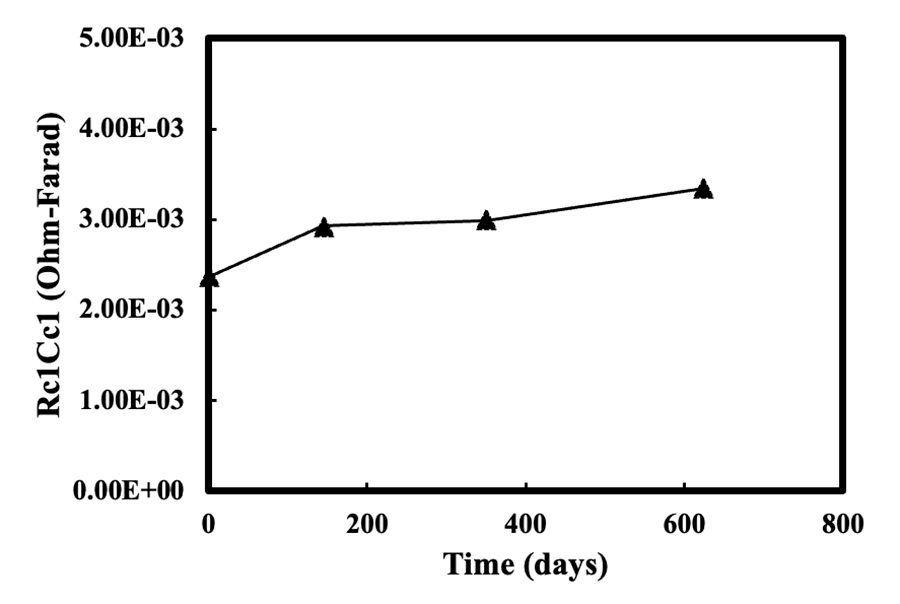

The surface corrosion on the steel pipe was tested for over 600 days. The surface index (RC) changed from 2.4 x 10-3 ΩF to 3.3x 10-3 ΩF, a 37.5 percent increase, as shown in Figure 14. This percentage change was less than what was observed in the 3.5 percent salt water, which varied from 220 percent to 275 percent.

Figure 14. Corrosion index parameter for the steel pipe surface in clay soil

Conclusions

In this study, the new nondestructive rapid detection and quantification of corrosion was verified and compared with a standard test method using carbon steel. Based on this study, the following conclusions are advanced:

- The weight change in steel in 10 percent NaCl solution in one year was about 1 percent, and corrosion rate was 1.54 mm/year.

- The new nondestructive test separated the surface corrosion from bulk corrosion. The method clearly identified the resistivity to be a highly sensing material property to characterize the bulk corrosion in steel. The bulk resistivity increase in corroding steel in 3.5 percent salt solution in 500 days was over 4,430,00 percent, much more sensitive than the weight loss method.

- Also, a new corrosion index was developed and verified to characterize and quantify the surface condition on the corroding steel. The corrosion was different at the two tested points and the visual observation verified it. The corrosion index increase in corroding steel in 3.5 percent salt solution in 500 days was over 200 percent. The surface corrosion index in the corroding steel pipe in the moist bentonite clay was a 37.5 percent increase in 600 days.

- Based on the material property changes, the surface corrosion was less than the bulk corrosion in the salt water, based on the new test method.

Comments